2: Euler’s method.#

Numerical solutions to ODEs.#

Suppose that we want to compute a numerical solution to the first-order IVP

over the interval \([a,b]\). Choosing some positive integer \(n\), our goal is to compute a sequence of points \((x_i,y_i)\) so that if \(y\) is the true solution, then

for \(i = 0,1,\dots, n\). We say that there are \(n\) steps, or equivalently \(n+1\) mesh points or nodes. The distance \(h_i=x_{i+1}-x_i\) is called the \(i\)th step-size, which may be variable. For much of this course, however, we will use equally-spaced meshes with step-size \(h=(b-a)/n\).

Linearization and Euler’s method.#

Once the mesh points have been chosen, the most straightforward approach to computing the \(y_i\)’s is known as Euler’s method. It is the method that Katherine Johnson and her team used to compute (mostly by hand) the path that the Apollo astronauts would follow to land on the moon. The basis for Euler’s method is the tangent line approximation from calculus known as linearization. Recall that if \(y\) is differentiable at \(x=x_0\), then

when \(x\) is sufficiently close to \(x_0\). Therefore, if \(y\) is the true solution to the IVP (3) and \(h=x_1-x_0\) is small, then

Whence choosing \(y_1 = y_0 + hf(x_0, y_0)\), we have \(y_1\approx y(x_1)\) as desired. Continuing in this fashion, Euler’s method is defined by the recurrence

for \(i\ge 0\).

Python implementation.#

The math263 module contains the following Python implementation of Euler’s method.

import numpy as np

def euler(f, a, b, y0, n):

"""

numerically solves the IVP

y' = f(t, y), y(a) = y0

over the t-interval [a, b] via n steps of Euler's method

"""

h = (b - a) / n

t = np.empty(n + 1)

if np.size(y0) > 1:

# allocate n + 1 vectors for y

y = np.empty((t.size, np.size(y0)))

else:

# allocate n + 1 scalars for y

y = np.empty(t.size)

t[0] = a

y[0] = y0

for i in range(n):

t[i + 1] = t[i] + h

y[i + 1] = y[i] + h * f(t[i], y[i])

return t, y

Example.#

We now show how to use Euler’s method to solve the IVP

over the interval \([0, 2]\).

# load modules

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import sympy

from tabulate import tabulate

import math263

# define IVP parameters

f = lambda x, y: x**2 - y

a, b = 0, 2

y0 = 3

# use the Euler's method from the math263 module to compute numerical solution

n = 10

xi, yi = math263.euler(f, a, b, y0, n)

# tabulate the results

data = np.c_[xi, yi]

hdrs = ["i", "x_i", "y_i"]

print("Euler's method")

print(tabulate(data, hdrs, tablefmt="mixed_grid", floatfmt="0.5f", showindex=True))

Euler's method

┍━━━━━┯━━━━━━━━━┯━━━━━━━━━┑

│ i │ x_i │ y_i │

┝━━━━━┿━━━━━━━━━┿━━━━━━━━━┥

│ 0 │ 0.00000 │ 3.00000 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 1 │ 0.20000 │ 2.40000 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 2 │ 0.40000 │ 1.92800 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 3 │ 0.60000 │ 1.57440 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 4 │ 0.80000 │ 1.33152 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 5 │ 1.00000 │ 1.19322 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 6 │ 1.20000 │ 1.15457 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 7 │ 1.40000 │ 1.21166 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 8 │ 1.60000 │ 1.36133 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 9 │ 1.80000 │ 1.60106 │

├─────┼─────────┼─────────┤

│ 10 │ 2.00000 │ 1.92885 │

┕━━━━━┷━━━━━━━━━┷━━━━━━━━━┙

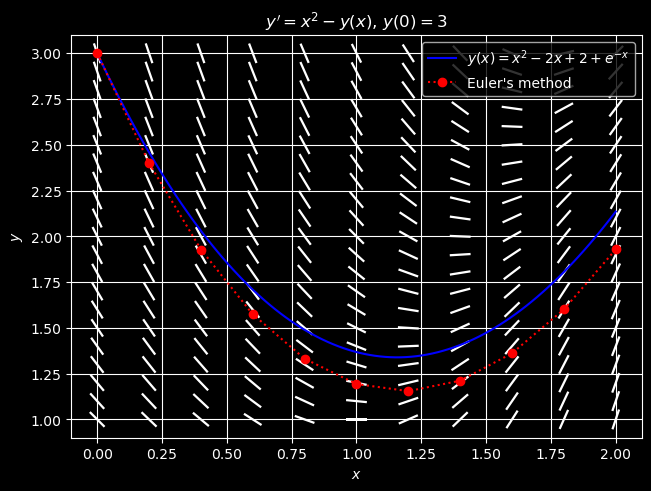

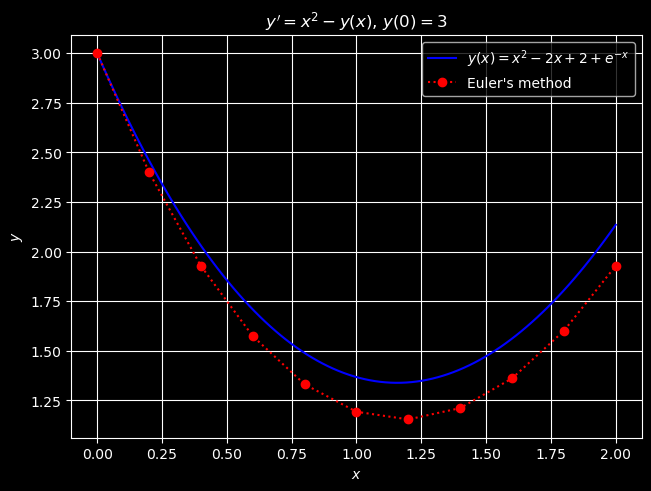

Since the IVP (5) can be solved analytically, we can plot the symbolic and numerical solutions together on the same set of axes.

plt.style.use("dark_background")

# solve the IVP symbolically with the sympy library

x = sympy.Symbol("x")

y = sympy.Function("y")

ode = sympy.Eq(y(x).diff(x), f(x, y(x)))

soln = sympy.dsolve(ode, y(x), ics={y(a): y0})

print("The function")

display(soln)

print("is the exact symbolic solution to the IVP.")

rhs = f(x, y(x))

# convert the symbolic solution to a Python function and plot it with matplotlib.pyplot

sym_y = sympy.lambdify(x, soln.rhs, modules=["numpy"])

xvals = np.linspace(a, b, num=100)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(layout="constrained")

ax.plot(xvals, sym_y(xvals), color="b", label=f"${sympy.latex(soln)}$")

ax.plot(xi, yi, "ro:", label="Euler's method")

ax.legend(loc="upper right")

ax.set_title(f"$y' = {sympy.latex(rhs)}$, $y({a})={y0}$")

ax.set_xlabel(r"$x$")

ax.set_ylabel(r"$y$")

ax.grid(True)

The function

is the exact symbolic solution to the IVP.

Note that although the sequence of errors \(e_i = |y(x_i) - y_i|\) is not necessarily increasing, there is a tendency for the errors made at previous steps to build up at subsequent steps.

Below we overlay the plot with a direction field plot for the ODE of (5). This helps us to see that every pair of of points \((x_i, y_i)\), \((x_{i+1}, y_{i+1})\) approximates the true solution to the ODE that passes through the point \((x_i, y_i)\), but not necessarily the solution to the given IVP which passes through the initial condition point \((x_0, y_0)\).

# set window boundaries

xmin, xmax = a, b

ymin, ymax = 1, 3

# set step sizes defining the horizontal/vertical distances between mesh points

hx, hy = (b - a) / n, 0.1

# sample x- and y-intervals at appropriate step sizes; explicitly creating array of doubles

xvals = np.arange(xmin, xmax + hx, hx, dtype=np.double)

yvals = np.arange(ymin, ymax + hy, hy, dtype=np.double)

# create rectangle mesh in xy-plane;

X, Y = np.meshgrid(xvals, yvals)

dx = np.ones(X.shape)

# create a dx=1 at each point of the 2D mesh

dy = f(X, Y)

# sample dy =(dy/dx)*dx, where dx=1 at each point of the 2D mesh

# normalize each vector <dx, dy> so that it has "unit" length

[dx, dy] = [dx, dy] / np.sqrt(dx**2 + dy**2)

# plot direction field on top of previous plot

plt.figure(fig)

plt.quiver(

X, Y, dx, dy, color="w", headlength=0, headwidth=1, pivot="mid", label="_nolegend_"

)

plt.show()